Written by Matthew Campelli

From athlete performance, to referee calls and spectator health – poor air quality is rocking the fundamental pillars of professional sport.

Sport has an air pollution problem. A big, overwhelming and invisible elephant in the room, air pollution’s intangibility has made it an easy issue for sports team owners and administrators to ignore.

But a growing body of research is beginning to paint an uncomfortable picture – that there is a significant link between air quality and some of the fundamental pillars of professional sport.

Athlete performance and longevity. Big calls made by referees and umpires. Spectator health and satisfaction. All are being negatively impacted by poor air quality. And while the effect on sport is becoming all too obvious, the fact that sports events generally increase air pollution in a location through traffic and fan activity exacerbates the issue.

With research in this area still in its infancy, and evidence of sports organisations tackling the issue rare, what can sport do with current research and examples to mitigate the negative impacts being exposed?

Athlete performance and longevity

Firstly, it’s important to define what air pollution is. According to both the United States Environmental Protection Agency and European Environment Agency, there are six common air pollutants: ground level ozone (or smog), particulate matter (such as PM2.5 or PM10), NO2 (that comes from the burning of fuel), carbon monoxide (from vehicles burning fossil fuels), lead pollution, and sulphur dioxide.

All are harmful to human health to varying degrees. If, for instance, a person has chronic asthma or other respiratory conditions, negative reactions to poor air quality can be pronounced. Athletes, because of their higher rate of breathing during exercise and increased airflow velocity, are also a disproportionately affected group, according to a study carried out by World Athletics, the sport’s international governing body.

There are suggestions that elite sportspeople are beginning to notice a correlation between air quality and their health and performance. During the wildfires that ravaged parts of California in late-2018, LeBron James complained of suffering headaches ahead of the LA Lakers’ NBA match with the Sacramento Kings.

James’ teammate Kyle Kuzma told ESPN that “breathing, it’s a little bit muggier.” And these are athletes plying their trade in an indoor environment.

Despite emerging victorious from this year’s Australian Open, tennis icon Novak Djokovic said that if air conditions continued to deteriorate around Melbourne due to closeby bushfires, the competition organisers would have to think about creating rules to accommodate it. He also complained that China was the “worst in terms of air quality.”

These incidents, although concerning for everybody related to sport, remain anecdotal. That’s why World Athletics has started to investigate to what extent athlete performance and longevity are being impacted by poor air quality by generating some data.

“We have plenty of information about the effect of air pollution on health. There’s no need for further investigation in that area,” Paolo Emilio Adami, the federation’s health and science department medical manager, tells The Sustainability Report. “We’re extending that to our context by asking the question: are athletes affected differently from a health perspective? And would their performance be impaired by air quality?”

To begin to answer those questions, a pilot study was conducted during the Yokohama World Relays to investigate the air quality inside the stadium and the training areas, which were located 300 metres apart. Fourteen air quality monitoring devices were set up in both locations to discover what pollutants were most prominent.

Alongside the measurement of air quality, a sample of athletes were asked to complete a survey asking them to compare the air quality in Yokohama with the air quality they experience when training in a home environment. They were also asked if air pollution was a concern to them – one-third said it was.

Clinical studies to explore the effect of air pollution were not conducted during the World Relays due to the nature of the competition (the event is a team, not individual tournament). The next step for World Athletics was to implement clinical studies during the World U20 Championships in Nairobi, Kenya, although, with the coronavirus crisis dominating global discourse, that event is almost certainly due to be postponed or cancelled.

For Nairobi, Adami’s team was preparing to adapt the questionnaire and measure the number of medical encounters of a respiratory nature during the week-long event. The team would then look at real-time air quality measurements to see if there was a correlation.

But, even with that information, drawing conclusions about which pollutant is worse for athletes remains a significant challenge.

“The problem is it’s very hard to isolate the effect of one pollutant against another,” Adami explains. “When we exercise outdoors we breathe a mixture of gases, particles or black carbon. They all interact together and may cause reduction in performance or symptoms.

“It’s hard to say if ozone is worse than NO2, for example. That’s why we are working through our events to understand if there’s an impact. What we’re doing is moving from a more general approach to focusing on specific athletes.”

A separate piece of research conducted by Andreas Lichter, Nico Pestel and Eric Sommer in 2015 suggested that higher levels of ozone and PM10 particles (particulate matter with a diameter of 0.01mm) affected the productivity of professional footballers in Germany, with productivity measured by the players’ number of passes and pass accuracy.

But there are variables. Just as Adami explains that different types of athletes (endurance, sprinter) can be affected differently by air pollution, Lichter’s research produced some evidence that younger footballers were not as affected by high levels of pollution as older professionals, and that physically larger players felt more of an impact.

Mental as well as physical

Nico Pestel’s work on the German football investigation inspired him and colleagues, Steffen Künn and Juan Palacios, to take it a step further: to look at the effect of poor indoor air quality on the performance of chess players.

After analysing 30,000 moves over the course of 596 games, the academic trio found that an surge in concentration of PM2.5 particles increased the players probability of making an erroneous move by 26.3%.

Whether chess should be classed as a sport can be debated in another article, but Pestel’s study may have ramifications for more traditional sports – that air quality can hamper athletes’ cognitive function as well as their physical attributes.

Think of all the times you’ve been to a game when, watching a seasoned professional find themselves in a promising scoring or passing position, you’re rendered speechless as they inexplicably give the ball away or become caught in two minds and robbed of possession.

It’s an all-too-common scenario, and one difficult to attribute to air quality alone. But based on the chess study findings it appears unlikely that air pollution had no impact at all.

And it’s not just the players. The work of James Archsmith, Anthony Hayes and Soodeh Saberian, ‘Air quality and error quantity’, explored how the decisions of Major League Baseball umpires were affected by air pollution. The research discovered that a 1ppm (parts per million) increase in carbon monoxide over a three-hour period caused an 11.5% increase in the propensity of umpires to make incorrect calls – an extra two erroneous calls per 100 decisions.

That may not seem like a lot in itself, but if a similar pattern were to occur in several games, across several sports, we’re talking about a large number of incorrect decisions. And that’s not even taking into account the context: these calls could occur during the championship game. Or it could be a last minute penalty awarded during the FIFA World Cup final. Leagues, cups and, ultimately prize money, could be hanging on these decisions.

Spectator health

The burning of fossil fuels, agricultural work, and emissions from factories and industry are among the greatest sources of air pollution. According to the World Health Organization, 4.2 million people die as a result of being exposed to this outdoor air pollution every year.

While sport, in general terms, is commonly associated with good health and fitness, going to watch a major sporting event can be anything but for spectators.

Much of the research in this article focuses on the negative effect air pollution has on the sports industry. But the fact is the sports industry is having a negative effect on air quality.

Nicholas Watanabe, an assistant professor at the University of South Carolina, has been investigating the link between air quality and sports events as part of a wider body of research focusing on sports economics and sustainability.

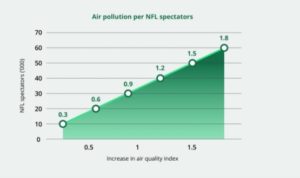

In a study he presented earlier this year, Watanabe found that for every 10,000 spectators that attend an NFL game, there was an increase of 0.3% on the AQI (air quality index). Ozone and NO2 were the two most prominent pollutants, which suggests the decrease in air quality relates to vehicle emissions from a larger number of cars.

Tailgate parties, commonly associated with American football, in which spectators park their trucks and set up grills ahead of the game (oftentimes several hours beforehand) also contributes to the amount of pollution generated by the event. And it’s not just American football.

“When Columbia hosted the NCAA basketball tournament in 2019, the AQI went up to like 150 or 160 in a city that’s usually hitting around 40,” Watanabe tells The Sustainability Report. “This was in the days before the games when people were driving in and, because it was hot, using their air conditioning.”

He adds: “We can see that there is a very strong pool of evidence that hosting sporting events does have an impact on the environment, especially when vehicle traffic is involved.”

But variables are also at play when it comes to fan health. While spectators in the US may be more prone to inhaling increased levels of ozone because of high levels of traffic associated with fan travel, people attending Chinese Super League games are, in general, more likely to be affected by PM2.5 particles.

In another study exploring the effect of air pollution on Chinese Super League attendances, Watanabe found that poor air quality was not a deterrent for people attending matches, even though the “potential health damage that can result from such habitual consumption cannot be understated.”

Several Chinese Super League clubs play in cities with some of the worst air pollution rates in the world, such as Beijing, Guangzhou and Shanghai. According to Watanabe, vulnerable populations of football fans, such as those with asthma and other underlying health conditions, attending Chinese Super League matches may “facilitate growing disparities of health” among different groups of sports consumers in the nation.

What can sport do to address poor air quality?

One thing is clear: the coronavirus outbreak that has dominated the global news cycle for much of 2020 has altered our perception of health, particularly in more developed nations where, once taken for granted, good human health has become something to truly cherish.

A number of sports organisations have played a small but symbolic role in the global recovery. Mercedes’ F1 team has been manufacturing ventilators. Stadium owners have offered their venues as emergency healthcare facilities. Could the industry take a leading role in finding solutions to other major issues of this type, such as poor health accelerated by air pollution?

Although clinical trials looking at the effects of air pollution on athlete, official and spectator health are currently scarce, the pieces of research cited in this article have presented a number of recommendations sports organisations can adopt to mitigate the negative impacts.

1. Measure venue and location air quality before the event

Adami says that one of the most proactive measures sports organisers can do is measure air quality for a period of time before events so that they can schedule matches and competitions during a time where air pollution is less present.

World Athletics’ Yokohama study revealed that studying the “hourly variability” of pollutants was a good way to find optimal training and competing periods. For example, during the World Relays, it was discovered that those training after 5pm had a better chance of practicing in cleaner air.

Ideally, the air quality of the event location would be monitored over the same period one year before so that events and training opportunities can be planned at the best times. Although for some sports (regular leagues matches in different locations with multiple stakeholders) this could be complicated.

“It’s not one size fits all,” says Adami. “Each location has its specificity and characteristics. The days when the standards were applied to all are gone. We need to individualise.”

According to Adami, measuring air quality in a similar fashion to World Athletics’ Yokohama project would not be beyond the financial reach of major sports organisations, although an investment in time is needed.

Meanwhile, in South Korea, the football governing body has taken steps to protect players and fans from poor air quality by allowing match officials to postpone any games when the nation issues a ‘fine dust warning’ (when dust concentration reaches 300 micrograms per cubic metre).

2. Formulate a clean transport policy

Ozone and NO2 derived from vehicle emissions are a significant factor in pollutants found around sports venues, particularly in the NFL where tailgate parties form part of the gameday experience.

Watanabe explains that one method to combat this is to incentivise the use of public transport, perhaps with the use of a combi ticket that allows match ticket holders to use buses, trains and trams for free on the day of the game.

Some football clubs in Germany have implemented this policy. It was also used during the Gulf Cup in Qatar in December last year and was one of the flagship climate policies for the 2020 UEFA European Championships, which has since been postponed until 2021.

But Watanabe suggests that incorporating such policies could be difficult in the US.

“It’s fine if you have a public transport network, but in the US a lot of these stadiums are out in the suburbs in difficult to reach places, thus everybody tends to drive,” he says. “When a team builds a stadium the first thought isn’t ‘let’s build a light rail’, it’s ‘we need a highway exit closer’. It’s about getting cars out faster.”

3. Make air quality a key part of your strategy

The incentive for sports team owners and other sporting organisations to take action on air quality is two-fold, says Watanabe: firstly, it’s the opportunity to be ahead of the curve. It’s about setting a new standard and showing fans and athletes that they care about their health, particularly in the context of collective vulnerability felt in the midst of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Secondly, it’s an opportunity to convince athletes to come and play for you by showing them that the organisation cares about their health and has policies in place to aid career longevity.

“With an increase in AQI, the risk of cancer and other pulmonary diseases go up,” Watanabe explains. “Today you’re a strong, healthy athlete, but 10 years down the line you have lung cancer. To show foresight and care is important.”

During the unveiling of its recently-published 10-year sustainability strategy, World Athletics president Seb Coe said athletes and fans “expect more from us than good governance. They expect us to be global citizens, to take a leadership role in issues that affect the wider world and their communities.”

The federation’s blueprint includes “six key pillars”, of which local environment and air quality is one. As part of that commitment, World Athletics is aiming to install air quality monitors at each of its certified tracks around the world, and make real-time air quality data available to recreational runners as well as elite athletes so that they can make informed decisions about the times they train.

4. Look at your venue

One of the most noteworthy findings from World Athletics’ Yokohama study was the difference in air quality between the stadium and the training facility, despite the two venues being only 300 metres apart. Air quality in the exposed training area was worse than the air quality in the stadium, revealing to some extent the protection athletes and fans had due to the high stadium walls.

In his study on air pollution and the Chinese Super League, one of the recommendations Watanabe makes is for stadium owners to transform current venues into “domed facilities” to reduce athlete and spectator contact with air pollution during the match.

Despite this work being described as a “simple retrofit”, Watanabe acknowledges that such endeavors could be expensive, estimating an average cost of $200m for that kind of work. And, as LeBron James and Kyle Kuzma demonstrated, even a state-of-the-art indoor venue can’t always protect players and fans from feeling the effects of poor air quality.

5. Work with local authorities

With poor air quality contributing significantly to poor public health and mortality rates, it stands to reason that local authorities are intent on reducing air pollution and improving the health of their residents, thus reducing the strain on hospitals and health facilities.

A large proportion of stadiums and sports venues in the US have received public funding and, with four out of 10 cities having unsafe air, working with these facilities to improve the air in their local vicinity would make a lot of sense.

Since establishing its air quality pilot in 2018, World Athletics has worked with cities on a handful of projects. Once described as the “most polluted city on the planet” Mexico City collaborated with the governing body during its 2019 marathon to measure the air quality around the course, supplying its own data to complement the data of World Athletics to paint a full picture of the situation.

Adami explains that other event host cities are approaching World Athletics about implementing similar projects in their own localities to create an “environmental legacy” that remains long after the curtain comes down.

“Budapest will host our 2023 World Championships and the city has a very green-oriented mayor (Gergely Karácsony). When he heard about our interest in air quality he jumped on it,” Adami adds. “We are very happy to share our experiences with city councils. We believe this can be a very important legacy that all people living in the city should benefit from.”

Find value in the article? Get more content like this to your inbox, every week here.